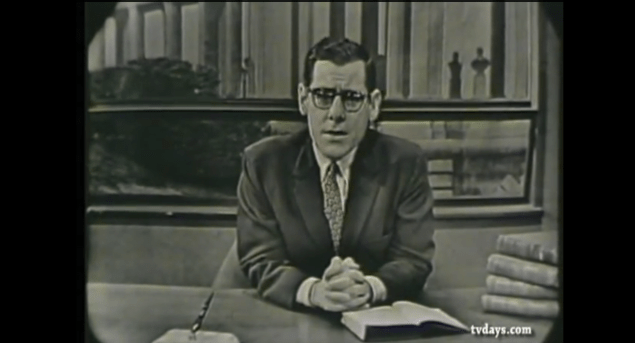

Starting in 1957, New Yorkers could turn on the TV at 6:30 most summer mornings to watch Sunrise Semester on CBS. The show’s “stars” were NYU professors, usually seated at a desk, lecturing on a given subject, such as history, philosophy and comparative literature. Viewers unable to afford the cost, or time, required by a traditional institution had the option to pay a reasonable $25 per point to follow along and receive credit.

Sunrise Semester, which went off the air in 1982, was the low-tech grandparent of the MOOC, or “massive open online course.” MOOCs, which many universities now offer, enable students to watch videos of classes, take tests online and sometimes pay for credit. MOOCs, many education policy wonks had hoped, would disrupt conventional education, offering the benefits of globalization at the tips of our fingers and profoundly expand access to academic knowledge.

Unfortunately, the free courses have yet to live up to that promise.

"The lecture in-person is just an on-campus MOOC,” NYU's Robert Ubell told the Observer. “They’re both ancient in style." |

To explain why, let’s rewind two years when several major universities, including Duke, Cornell and Columbia, started offering free online courses and The New York Times proclaimed 2012 “The Year of the MOOC.”

The pendulum of popular opinion swung dramatically from the opinion that the classes would revolutionize modern education, toward the notion that they are less transformative.

Robert Ubell, vice dean of Online Learning at New York University’s Polytechnic School of Engineering, describes the exploration of online learning as his life’s work. MOOCs, he argues, represent everything that’s wrong with lecture-style courses, only at Internet scale. The same common criticisms of the traditional lecture—the lack of engagement, the inability to give each student the requisite amount of personal attention—are also true about many free online courses.

“The lecture in-person is just an on-campus MOOC,” Mr. Ubell told the Observer. “They’re both ancient in style.”

Online education can feel alienating and stodgy as in-person lectures, only with the ability to click away at the first sign of boredom. Besides, sitting alone at a computer watching a video lecture is no different from amphitheater-style study halls, only you can close the browser rather than slip out the back door.

The biggest problem with MOOCs is holding onto students, suggested Georgia Tech assistant professor Karen Head. She recounted last year in The Chronicle of Higher Education her disappointment teaching a MOOC entitled, “First-Year Composition 2.0.” More than 15,000 students signed up for the course, but only 238 earned a certificate.

Technology caused much of the friction, noted Ms. Head. Students abandoned her course at first sign of resistance, whether it was downloading course materials or going through the peer-grading process that Internet scale makes inevitable.

Technology, ideally, should be fueling the education revolution, but Mr. Ubell argues the de facto benefits of high-tech are thin if that technology isn’t leveraged to increase engagement. In fact, if you don’t count Sunrise Semester, NYU has never dipped its toe into those waters.

There’s still some merit in evangelizing the greatest lecturers of our time and recording them for posterity, and MOOCs have brought academic superstars into every home that will have them.

MOOCs give a university visibility, allowing their most TED-friendly professors to stage an elaborate song-and-dance to prove to prospective students that their university can prepare them for a digital-first world, simply by dint of throwing courses on the Internet. |

Recorded lectures give us access to celebrity professors, such as Dan Ariely, the behavioral economist who will spend up to 11 weeks blowing your mind about rational decision-making. Or the entertaining classes of MIT’s world-famous physics professor Walter Lewin, notorious for his circus-like stunts such as swinging on a wrecking ball to demonstrate conservation of energy.

But it doesn’t take a wealth of scientific research to convince anyone that active learning with exercises, classroom discussions and one-on-one tutoring are more effective delivery methods than passive absorption. Nevertheless, that wealth of scientific research exists. A

2014 study of STEM courses published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that the fail rate for lecture-based courses was 55 percent higher than classes with approaches encouraging engagement.

The vast majority of people signing up for MOOCs are simply window-shopping—signing up for courses with good intentions—the academic version of New Year’s dieting resolutions (often abandoned for the first available cronut). Only 10 percent of all students who signed up for a MOOC viewed lectures, did homework and received grades, reported the study.

One of the best predictors of success for people enrolling in online courses is whether someone had to pay for it, which makes people much more likely to follow through.

“Paid graduate programs,” said Mr. Udell of NYU, “have a 90 percent completion rate, as opposed to only 5 percent or so [in the case of MOOCs].”

To capture students who could be served with online tools, universities must do more than simply post videos of lectures and make the tests available to anyone, says Daniel Huttenlocher, dean and vice provost of Cornell Tech who studies online education.

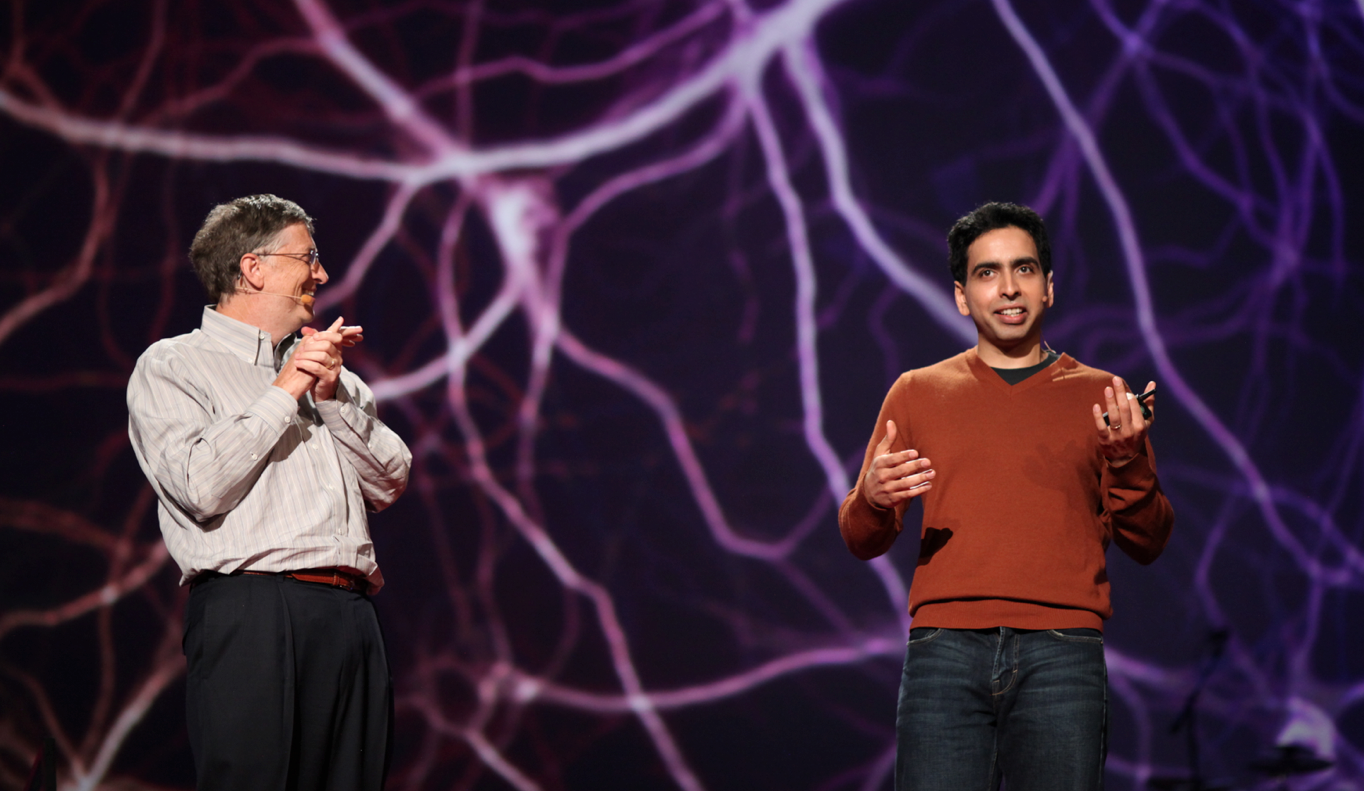

“Faculty have to rethink the material so that content delivery is interwoven with interactivity,” Mr. Huttenlocher said. “Like some of the attempts that the Khan Academy guys are making: Short snippets of video coupled with a lot of interactive exercises. I think that’s certainly the direction things are going in.”

Mr. Huttenlocher wasn’t the only person to cite Khan Academy, an online grade school of sorts that produces brief video lectures and automated quizzes to teach everything from basic geometry to macroeconomics, as the touchstone example of effective online education. Khan Academy encourages engagement-using games—students earn badges for skill mastery and answering others’ questions, which gives Khan’s younger audience a dopamine hit for micro-achievements.

For now, the best application for MOOCs has nothing to do with the students themselves, but recruitment and marketing. MOOCs give a university visibility, allowing their most TED-friendly professors to stage an elaborate song-and-dance to prove to prospective students that their university can prepare them for a digital-first world, simply by dint of throwing courses on the Internet.

“MOOCs are great for marketing,” Mr. Udell said. “But that’s just capitalism, and a convenient, easy way of doing things—just not for actual education.”